Introduction:

After the country icon’s death, his big hits such as Okie From Muskogee are getting all the attention, but it was his little known album from 2000 – released on a punk label – that was his last great outlaw statement

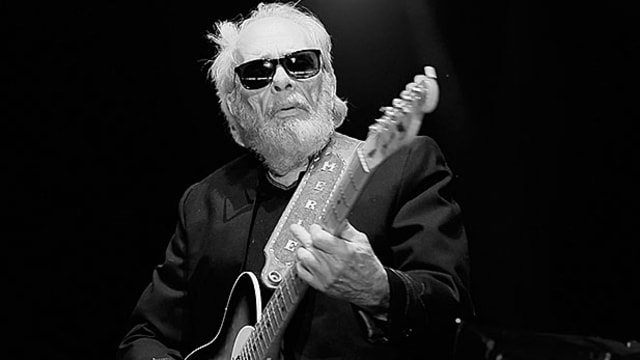

Merle Haggard died today. I have more than 30 of his albums; if he’s not my favorite musician, he’s very close. I love his first big hit, All My Friends Are Gonna Be Strangers, with his elastic phrasing sliding over those familiar honky-tonk changes. I love his classic 60s shimmering Bakerfield outlaw epics such as Mama Tried. I even adore slick 80s tracks like Call Me, where his voice catches against the easy listening background. But for me, his best album is his last great one: If I Could Only Fly, released in 2000.

At the end of the 90s, Haggard’s career was going nowhere. He had to file for bankruptcy in 1993; his label, Curb, had so little interest in him that it released multiple albums without cover art or titles – the albums 1994 and 1996 each showed only the year of release and Haggard’s name on an otherwise plain cover. Desperate for a change, Haggard signed with the punk label Anti.

The result certainly wasn’t a punk album. Nor was it exactly a return to Haggard’s Bakersfield roots. There were touches of his 80s AOR efforts, but the backing was more stripped down – leaning towards a kind of pristine folk.

That may not sound especially appealing, but Haggard’s singing makes it. As a young man, his vocals had been among the purest in country, with impeccable, inventive phrasing that at times even surpassed the supple, gulping glory of his hero Lefty Frizzell. But by 2000, when Haggard was 63, much of the sinew and effortless snap had gone out of his voice. You can hear him labor on Wishing All These Old Things Were New, as he draws out the phrases. “If I could start all over/I would still do what I do-ooo-ooo”. It’s staggered and a little breathless.

But the imperfections are what make it. Wishing All These Old Things Were New is one of many songs about ageing, death and loss on If I Could Only Fly. The song starts with Haggard, who once sneered at marijuana use, regretting that he no longer does cocaine. Over a guitar line that recalls the Bakersfield days, slowed down, Haggard muses: “Watching as some old friends do a line/Holding back the want to in my own addicted mind/Wishing it was still a thing that you and I could do-ooo-ooo/Wishing all these old things were new.” The regret is not just about drug use, but also Haggard’s own stronger past (“Good times like the roaring 20s, and the roaring 80s too”). He can’t sing like that any more, so he has to sing like this. And he’s not especially happy about it.

Not all the songs are regretful or solemn, but all are aware of history and time. The traditional New Orleans-jazzy Honky Tonky Mama is a lascivious stomp, which the band takes at a sedate pace so that Haggard’s vocals can keep up. “If. You. Fool. Around. Those. Honkies. You. Will. Never. Get. It. Back,” he sings, with a period after each word, letting you know that the older Haggard is a more careful man, or at least is pretending to be for the moment.

The swinging Proud To Be Your Old Man has a similarly jaunty western swing feel, as Haggard addresses his fifth and last wife, Theresa Ann Lane. “There’s a lotta young men who covet your love,” he boasts, with a drop on the last word that shows he can still sing better than most of those whippersnappers. And if he wavers on the words “it’s amazing how you understand”, that’s only to show that, as the song says, he doesn’t need to be perfect.

The masterpiece of the album, though, is Blaze Foley’s title track. Haggard had been singing it for a long time; a 1986 performance shows Haggard with his vocal mastery intact, lifting the lyrics up with an assured melancholy. It’s superior, accomplished schmaltz – a genre beloved by every country music fan.

The version of the song on If I Could Only Fly is something else, though. Haggard’s voice strains on the very first line: “Almost felt you touching me just now/I wish I knew which way to turn and go.” In the earlier performance, he was channelling and expressing grief; here, it feels as though the grief is clotting around him, and he’s trying to dig out. Once, when Haggard sang If I Could Only Fly, the point of the song became that he could – his voice soared up, in control, ready to go wherever he sent it. But here, instead, he stalls and wavers off key. The old, young Merle Haggard was too good to express weakness convincingly.

Haggard’s voice continued to weaken over the last 16 years of his life, past the point where I, at least, could listen with much pleasure. If I Could Only Fly is getting on in years itself at this point, but it remains the last great Merle Haggard album, in part because it looks ahead with such clear eyes to this moment, when we know there won’t be any more.