Introduction:

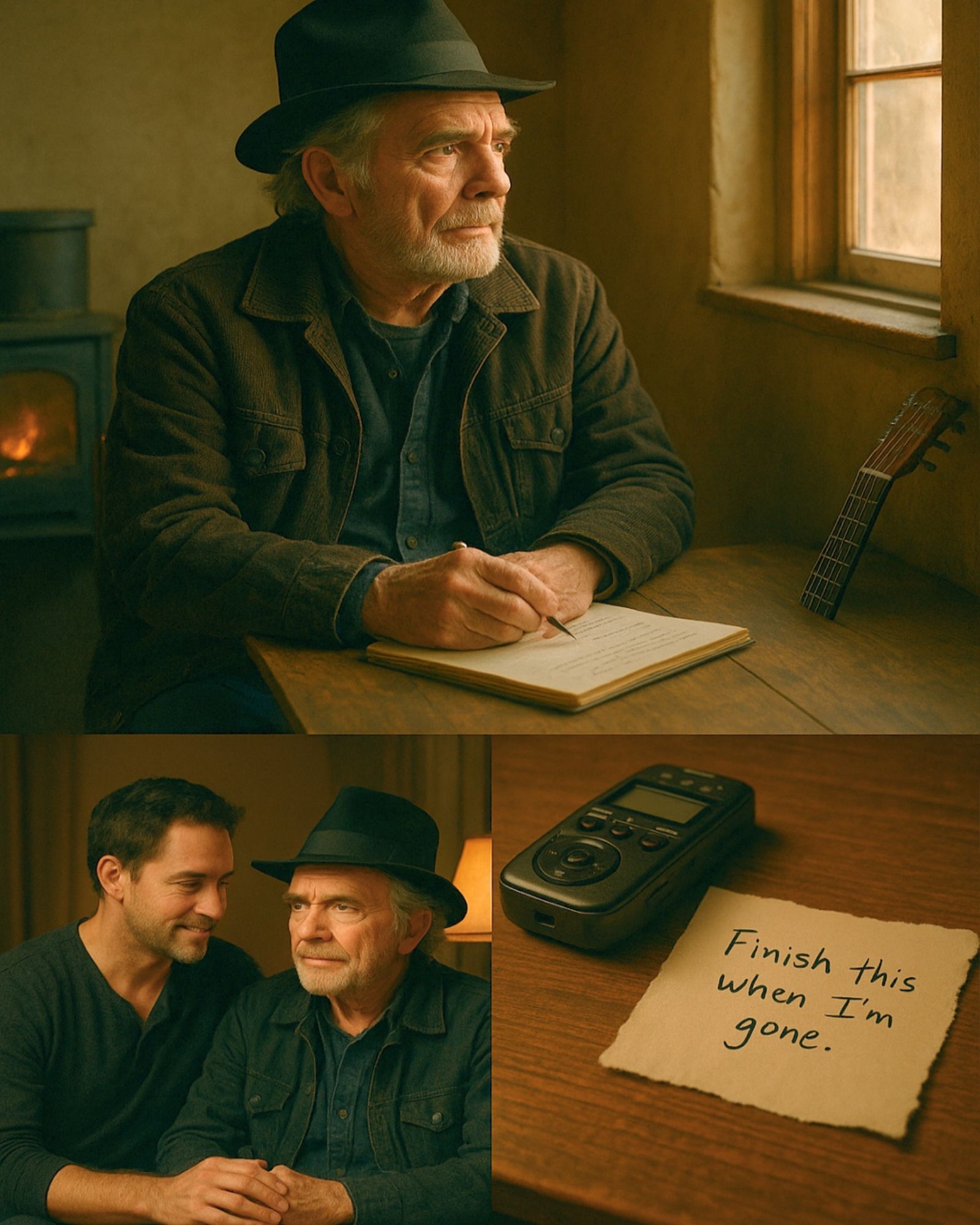

Late in the winter of 2014, while the world continued to see Merle Haggard as the outlaw poet of American country music, he spent most of his days in silence—tucked away in a small writing room behind his home in Palo Cedro. It wasn’t a studio built for legends. It wasn’t even the kind of space that suggested greatness. Wood-paneled walls, a tired heater humming in the corner, and an old guitar resting on the desk like a loyal companion—that was all. But that little room had held decades of Merle’s life: triumphs, heartbreak, reinventions, and the kind of private confessions that never reach a microphone. And that winter, something deeper was stirring.

He had a melody he couldn’t shake—slow, wandering, as gentle as footsteps pressing into fresh snow. It followed him everywhere, tugging at him, refusing to fade. Yet every time he tried to give it words, he stumbled in the same place: the second verse. He finally confided in a close friend, offering just five words that carried far more weight than they seemed: “It’s too close to home.”

This wasn’t about writer’s block.

It was about truth—the raw kind that pricks the heart when you get too near it.

For months, he circled that unfinished lyric like a man pacing the edges of a memory. He’d hum the tune, scribble a line or two, then shut the notebook. Some days he didn’t write at all. He just sat, gazing out the window, thinking about roads he’d traveled, regrets that never quite loosened their grip, and people he loved in ways too complicated for plain language. It was less a song and more a mirror, and Merle wasn’t sure he was ready to look straight into it.

Then came a quiet night that changed everything.

After a long conversation with one of his sons—a talk that began with laughter and drifted into honesty—Merle returned to that little room. He didn’t warm up his voice, didn’t search through lyrics, didn’t prepare. He simply picked up the guitar and let the truth speak for itself.

His voice was rougher now. Softer too. But beneath the gravel was something new: acceptance. The song finally took shape—not flawless, not polished, but real in a way only a lifetime can carve. He never performed it onstage. Never recorded it for an album. He played it only twice, both times in his living room, with no audience except the walls that had heard every version of the man he’d been.

After his passing, his family sorted through his belongings tenderly. In a small drawer, they discovered a handheld recorder labeled in Merle’s own handwriting: “Finish this when I’m gone.” On it was the demo—raw, shaky, breathtaking.

Some songs are made for charts.

Some are made for crowds.

And some, like this one, are made for the quiet spaces where truth whispers.

In its own way, the song was finished—not by edits or chords, but by the journey of the man who wrote it. When his family played it back, they didn’t hear sorrow. They heard Merle—one final time—telling the truth exactly as it lived in him.

An unfinished song that, somehow, said everything.