Introduction:

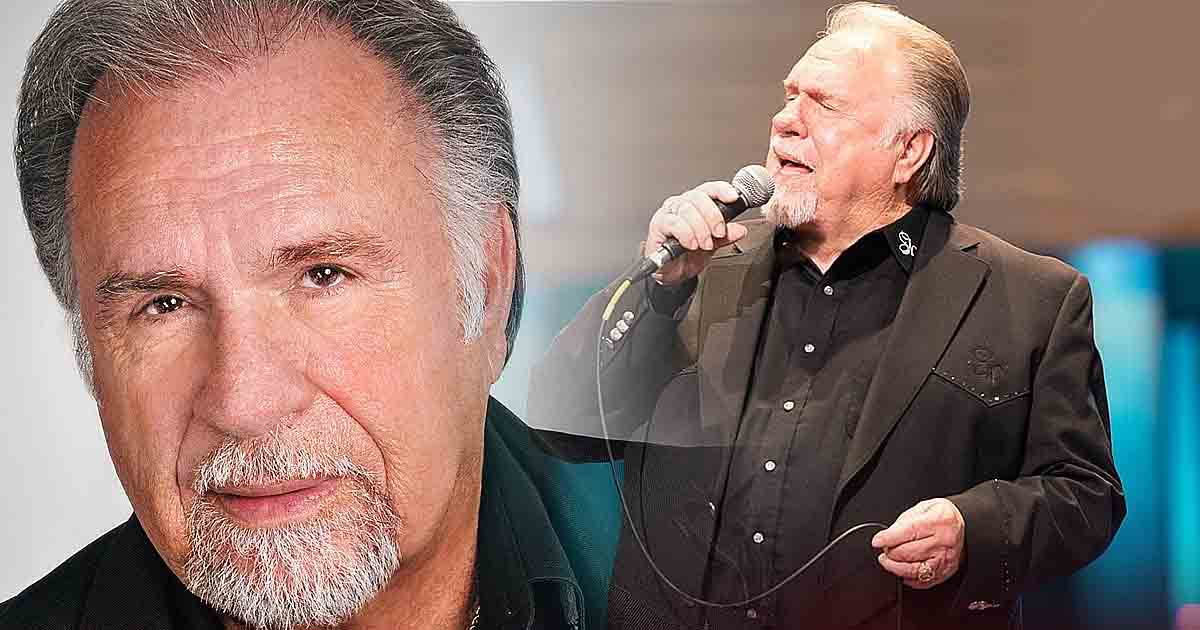

In a smoke-filled bar in Texas, where laughter once rose above the clinking of beer glasses, a single voice cut through the haze and brought the room to a standstill. The man singing was not a polished Nashville star, but a grease-stained mechanic named Gene Watson. His tone was plain yet powerful, carrying a depth that silenced even the rowdiest crowd. Few in that room could have imagined that this humble working man would one day step onto the sacred stage of the Grand Ole Opry, becoming one of the most revered voices in traditional country music.

Born on October 11, 1943, in Palestine, Texas, Watson grew up in stark poverty. He was one of seven children in a family that often struggled to secure even the most basic necessities. At times, they lived in an old converted bus, the wind slipping through its cracks during bone-chilling nights. Meals were uncertain, and hunger was a familiar companion. Yet amid hardship, resilience took root. From his father, Watson inherited an unyielding work ethic; from his mother, who played gospel songs on an old guitar after long days, he inherited music’s quiet flame.

As a teenager, Watson left school to help support his family, working in auto repair shops by day and singing in small bars by night. In the early 1960s, he recorded his first single at his own expense. It went largely unnoticed, but it marked the beginning of a journey defined not by instant fame, but by stubborn perseverance. For years, he balanced two lives: mechanic and musician, pouring his savings into recordings while performing in modest venues across Texas.

His breakthrough finally arrived in the mid-1970s with “Love in the Hot Afternoon,” a song that introduced America to a voice steeped in honesty and emotion. Soon followed classics like “Paper Rosie,” “Farewell Party,” and the chart-topping “14 Karat Mind.” At a time when country music leaned toward pop polish, Watson remained devoted to honky-tonk ballads that told stories of working-class struggle and quiet faith. His authenticity earned him the title “the singer’s singer,” admired deeply by peers and fans alike.

Yet success did not shield him from hardship. The rise of commercialized “New Country” in the 1980s sidelined many traditional artists. Then, in 2000, Watson faced a far greater trial: a diagnosis of colon cancer. Doctors urged rest, even retirement. Instead, he chose to fight. After surgeries and treatment, he returned to the stage within a year—thinner, perhaps, but vocally undiminished. His comeback was not merely professional; it was profoundly human.

Behind the spotlight stood his steadfast partner, Mattie Louise Bivins, whom he married in 1961. Their decades-long marriage and their children became his anchor through financial strain, illness, and the relentless demands of touring. Watson has often said that while music gave him a reason to sing, his family gave him a reason to live.

In January 2020, after more than half a century of dedication, Gene Watson was formally inducted into the Grand Ole Opry. The standing ovation that night felt less like applause and more like history acknowledging a debt long overdue.

Today, in his eighties, Watson still performs with a voice seemingly untouched by time. His life stands as proof that authenticity can outlast trends, that resilience can overcome tragedy, and that real country music—rooted in truth—never fades.