Introduction:

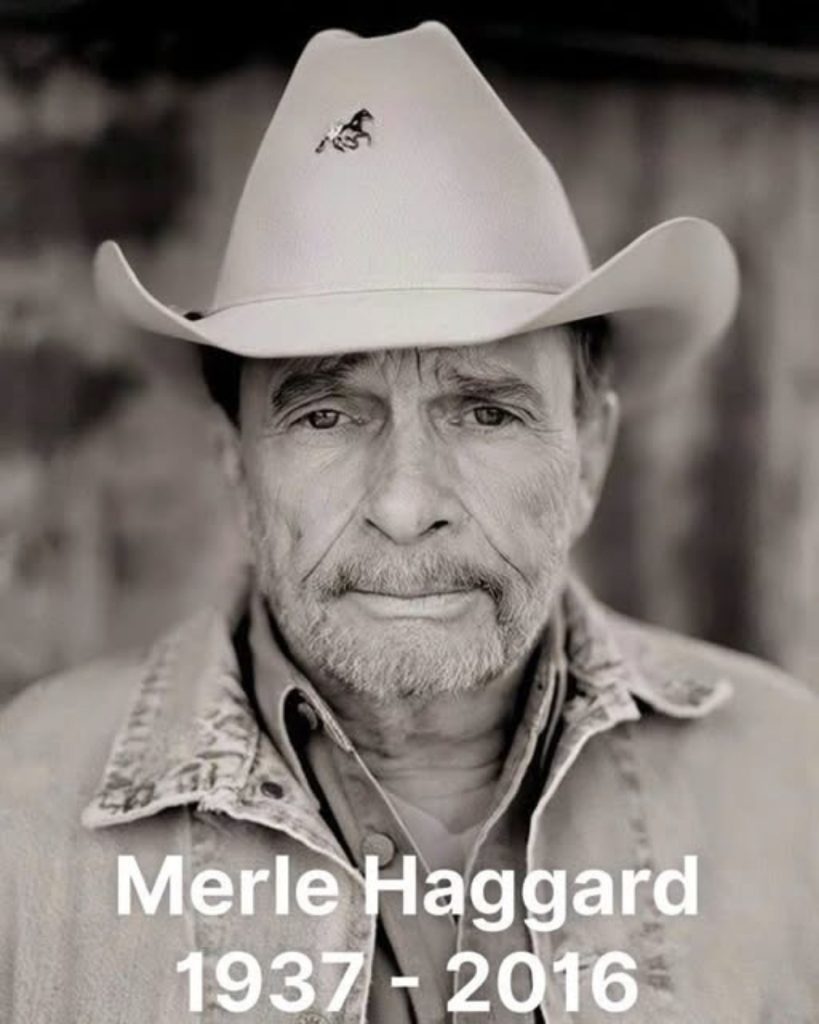

Growing up in a small town, I can still hear the soft crackle of my father’s old vinyl player as Merle Haggard’s “Kern River” drifted through the house. The needle’s hiss blended with the song’s mournful twang, and even as a child, I sensed this was more than background music. It felt like a lived memory set to melody—a story tied to a real place, a real danger, and an emotional truth I would only understand years later. “Kern River” remains one of country music’s most quietly devastating narratives, a song where landscape and loss become inseparable.

Released in July 1985 as the title track of Haggard’s fortieth studio album, Kern River stands firmly in the Bakersfield Sound tradition—raw, direct, and grounded in honky-tonk grit rather than polished Nashville gloss. Written and recorded with his longtime band, The Strangers, the single reached No. 10 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart. Yet its true impact goes beyond chart numbers. Inspired by California’s real Kern River—beautiful, unpredictable, and often deadly—the song tells of a young love cut short when the narrator’s girlfriend drowns, a tragedy that echoes through his life.

The track emerged during a tense period in Haggard’s career, as his relationship with CBS Records strained under industry pressure to chase younger trends. In his memoir My House of Memories, Haggard recalled defiantly standing by the song when executives doubted it. That conviction is audible. As biographer David Cantwell later described, it is “a scary record” that “screamed quiet and startled you alive”—an apt portrait of its restrained emotional force.

Musically, “Kern River” is a masterclass in understatement. Steel guitar weaves through a spare arrangement of fiddle, drums, and subtle electric guitar, creating a sonic landscape as open and haunting as the river itself. Haggard’s baritone—worn, steady, and edged with vulnerability—carries the narrative without theatrical flourish. The structure is classic country, but the mood is elegiac. Minor chords and measured pacing allow silence and space to speak as loudly as the lyrics.

Those lyrics are stark and unforgettable: “I’ll never swim Kern River again / It was there I first met her / It was there that I lost my best friend.” The river becomes both cradle and grave, symbolizing how the places that shape us can also wound us. The storytelling is regionally specific—rooted in Bakersfield—yet universally resonant. Grief, memory, and the impossibility of return are themes that cross all borders.

Over the decades, “Kern River” became a staple of Haggard’s live performances and a touchstone for fellow artists. Emmylou Harris and Dave Alvin both recorded moving covers, each honoring the original’s emotional gravity. Beyond music, the song has contributed to the cultural identity of California’s Central Valley, even intersecting with environmental awareness efforts tied to the real river.

Ultimately, “Kern River” endures because it speaks softly about the loudest human experiences: love, loss, and the way time changes our relationship with the past. It is a reminder that great country songs do not just entertain—they remember for us.