Introduction:

Barry Gibb’s story does not begin in applause or spotlight, but in survival. Born on September 1, 1946, in the humblest of rooms, his life started with the sound of coins counted on a kitchen table and a mother’s whispered prayers that supper would last one more night. His father, Hugh, was a drummer with calloused hands, and his mother, Barbara, was the quiet miracle that held a fragile family together. From those early years, the boy who would later move millions first learned the music of endurance.

At two years old, tragedy nearly silenced him forever. A teapot tipped, boiling water fell, and the house became a scene of chaos. Doctors predicted twenty minutes of life. His mother burned her own hands tearing away the scalding clothes; his father ran through the streets with a wounded child in his arms. Against every odd, Barry survived — scarred but unbroken. Those scars, decades later, would shimmer beneath the melodies he wrote, reminders that even pain can be poetic when it’s survived.

Childhood did not ease up. A stranger’s cruelty left invisible wounds that shaped his quiet, introspective nature. Yet amid instability and fear, sound became his anchor. In small rooms filled with hand-me-down furniture and hopeful noise, the Gibb brothers discovered harmony. Barry, Robin, and Maurice began singing around the table — their first concert, their first communion.

By eleven, Barry was leading the Rattlesnakes, performing in borrowed suits, chasing dreams to fill the cupboard. When the family emigrated to Australia in 1958, they carried nothing but faith and rhythm. They sang at speedways, their voices rising above the roar of engines — survival, again, set to song.

At fifteen, Barry chose music over school, knowing melody could feed where lessons could not. His writing sharpened like a blade: “I Was a Lover, a Leader of Men” announced him as a songwriter of rare instinct. Then London called. The Bee Gees were born — not a band, but a phenomenon. “New York Mining Disaster 1941,” “Massachusetts,” and “To Love Somebody” transformed three working-class boys into architects of emotion. Their harmonies were more than pop; they were prayers on vinyl.

Yet success carries its own storms. Ego, exhaustion, and heartbreak fractured the brothers. But reconciliation birthed their greatest songs — “Lonely Days,” “How Can You Mend a Broken Heart” — melodies that sounded like healing itself. Then came the resurrection: Miami, 1974, and a falsetto that turned survival into signature. “Stayin’ Alive” became not just a hit but a statement of fact.

When fame soured and backlash burned, Barry endured again — quieter now, but undeterred. The losses that followed were unspeakable: Andy, Maurice, Robin. Each death tore another piece of harmony away, until Barry stood alone, the “last man standing.” He carried their voices in his own, their laughter in his silence.

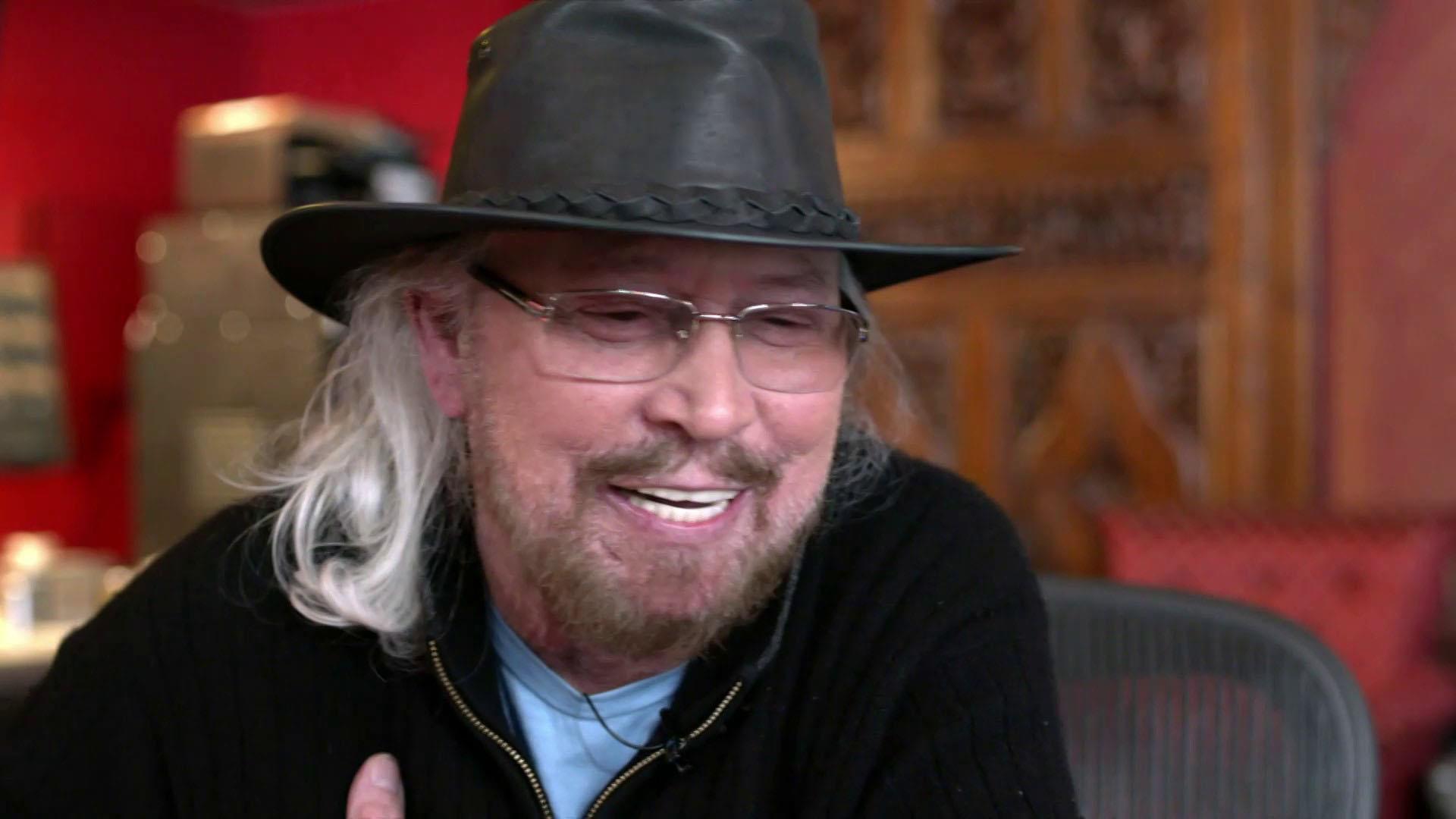

Today, behind the platinum plaques and serene Miami mornings, Barry Gibb is not simply a survivor of music’s brutal symphony — he is its conscience. He walks by the water, hands stiff from time, still writing, still singing. His songs remain not monuments to fame, but memorials to family, faith, and the fragile miracle of staying alive.

Because for Barry Gibb, survival was never the triumph. Love was. And that, still, is the song he sings.